Giorgio Griffa in his studio with four paintings from the Primary Signs cycle—photo

It was 1967–68 when Giorgio Griffa first started painting signs that “belong to any hand”—signs that still today are the hallmark of his work. Using water-based acrylic paints on loose, unprimed canvases (jute, hemp, cotton, linen) laid out on the floor, the canvases would then be pinned directly to the wall with tiny little nails along the top edge. He also painted with watercolors and inks on paper of different sorts.

Over the years, Griffa’s painting has branched out in new directions, creating what so far are thirteen cycles of works. Each cycle has a beginning; none has an end. As Giorgio himself explains, the cycles exist alongside each other. They are not stages of progression or regression, but simply continuous variations of becoming. Some of his works belong to more than one cycle, as the cycles are not a criterion of classification, but rather different pathways of work in the great big forest of painting. Pathways that sometimes cross and overlap each other.

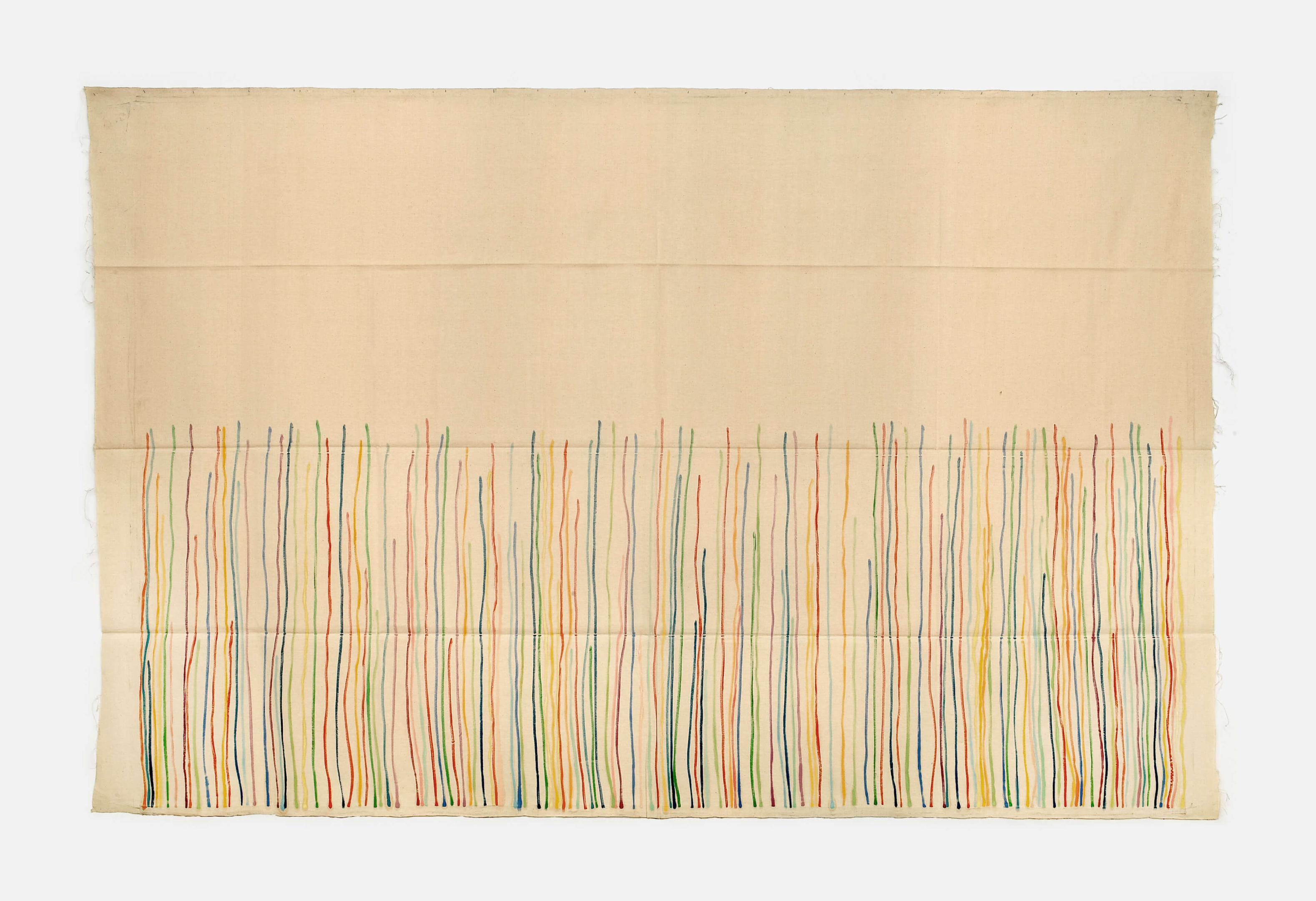

Primary Signs

Since late 1967, Griffa has painted lines—horizontal, vertical, and diagonal marks that are elementary signs. Signs that repeat themselves across the canvas without filling it up, creating a rhythm in space and time, just as humankind always has since the dawning of knowledge. Signs are way of knowing and thinking, bearing the age-old memory of humankind’s relationship with the world. This cycle introduced a number of constants seen in all of Giorgio’s later works—unstretched canvases, the unfinished aspect of the paintings, a non-hierarchical approach to painting, and the choice of anonymous signs that could belong to any hand, rather than identifying the privileged hand of the artist.

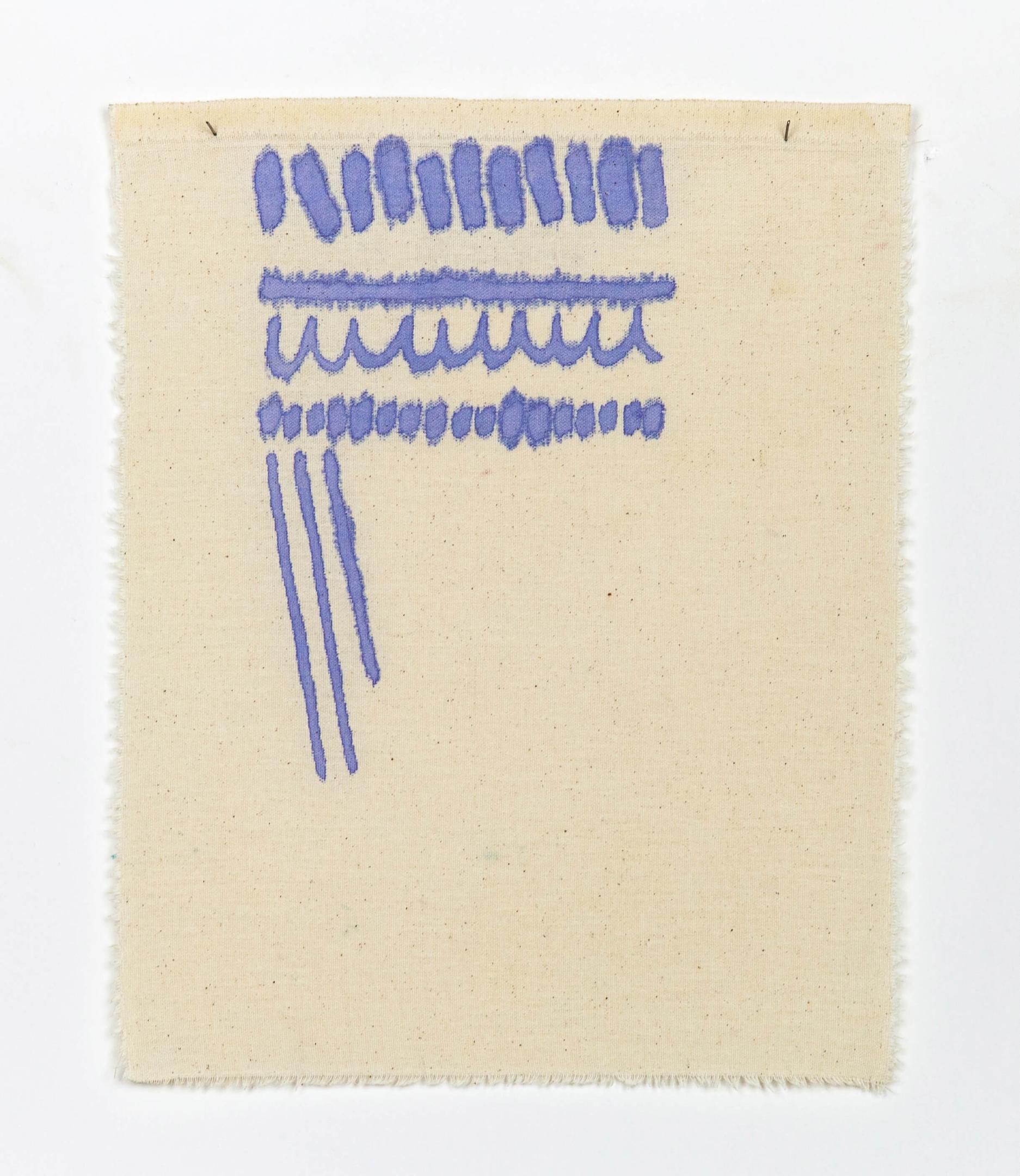

Contaminations

The Contaminations cycle was started in the late 1970s and shows various communities of primary signs living together on the one canvas and establishing various connections with each other. Here we see the influence of Matisse and his lights and colors of the Mediterranean, the search for “primordial contaminations,” and the great value placed on decoration, conceived not as a frill, but as rhythm, as a way of knowledge.

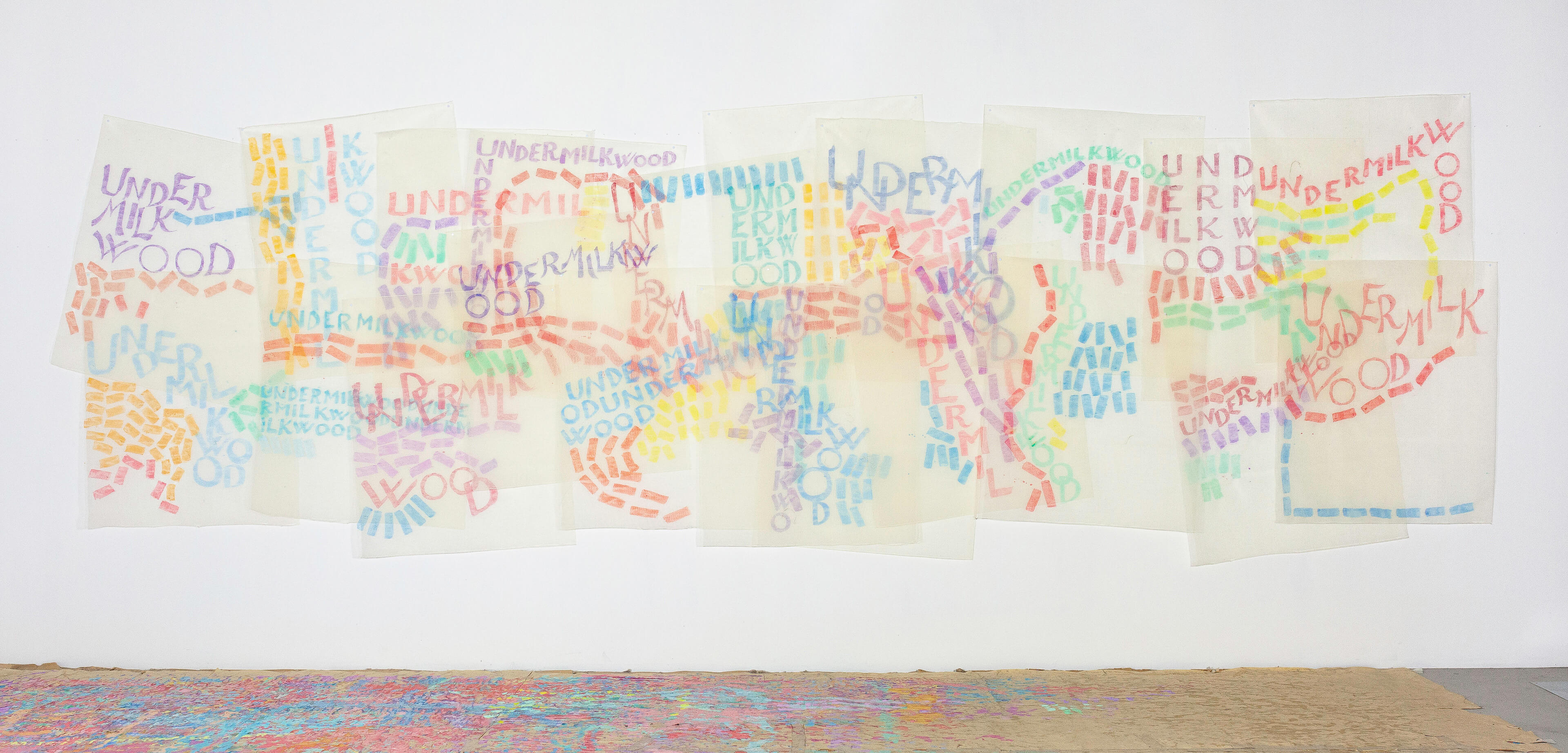

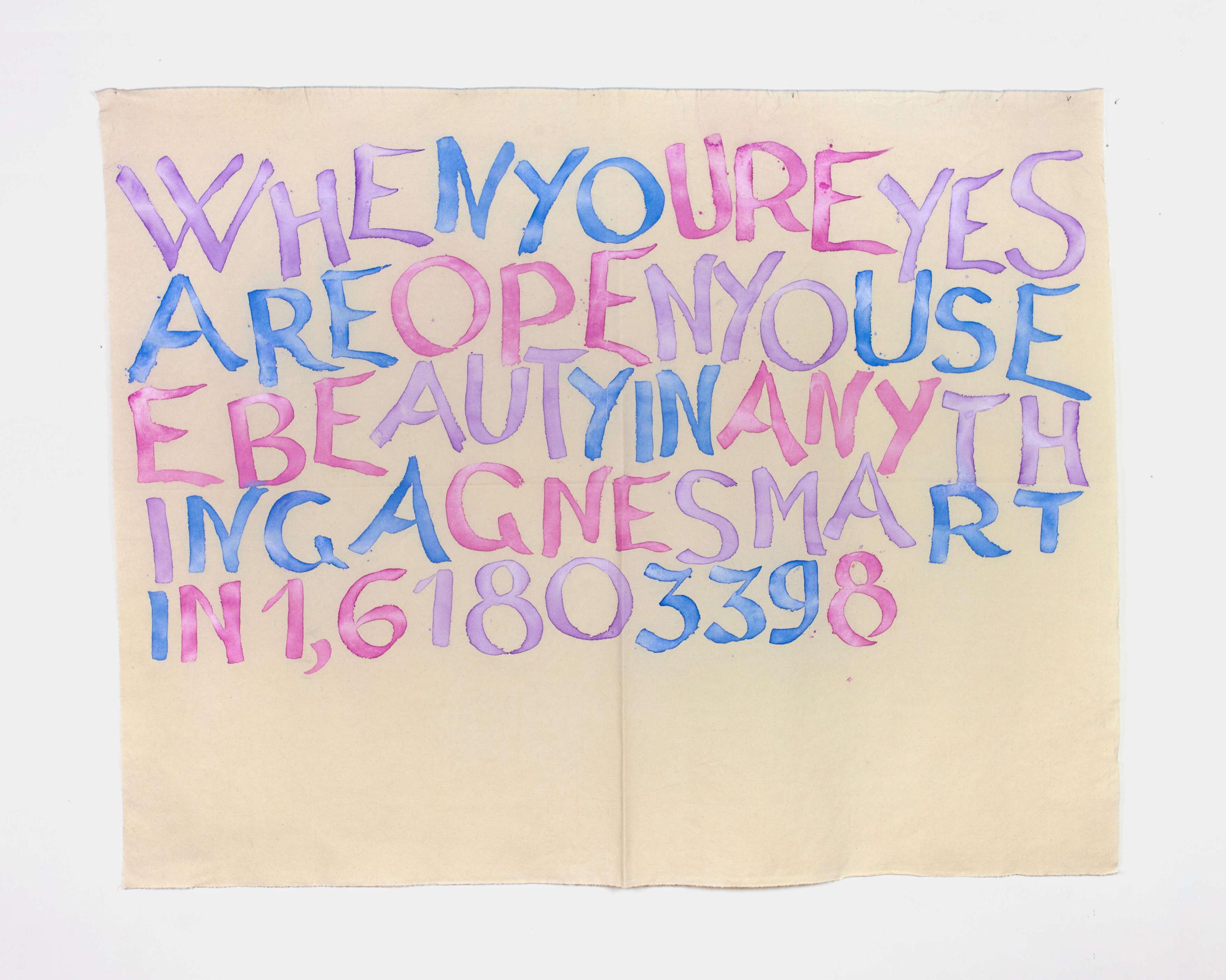

Alter Ego

In 1979, Griffa painted a triptych entitled Reflection, drawing inspiration from Matisse, Klein, and Klee. Originally conceived as an experience on its own, it instead became the first of a series of works belonging to Alter Ego, a cycle developed over the years drawing inspiration from various other artists, such as Paolo Uccello and Pietro Dorazio, Tintoretto, Joseph Beuys, Vincent Van Gogh, Philip Glass, Dylan Thomas, Agnes Martin, Ezra Pound, and Eugenio Montale. The works are tokens of love, presenting the conscious contradiction of using the signs of well-known names in the arts (painting, music, literature…) from the past and present as a catalyst and channel for producing signs belonging to no name.

Fragments

In 1980, Griffa produced a series of works using irregular fragments of painted fabric, arranged on the wall like stars and constellations. It marked the beginning of Fragments, a cycle that gives us a picture of the fragmentary nature of human knowledge and our limited understanding of the infinite complexity of the universe. Like with all of Griffa’s painting, shape and form are not an objective or focus of his work, but simply a consequence of the creative process.

Transparencies

This cycle emerged from a large work made for the 1980 Venice Biennale, consisting of twenty-one canvases that draw inspiration from the unclassifiable complexity personified in Dionysus. In this cycle, signs connect, they multiply and spread, join together and separate, and transform through the overlapping of transparent canvases, for the most part made of tarlatan, a fabric similar to the netting used to make ballerina tutus. Every time they are hung, the works in the cycle take on a new shape, as the canvases overlap in different ways, adapting to and connecting with the surrounding space.

Sign and Field

The introduction of colored backgrounds in the 1980s marked the start of the Sign and Field cycle, in which new concentrations of energy progressively enrich the artist’s work and expand the possibilities of his painting. In the works, the rhythmic succession of signs connects with the field, where big and small, full and empty live side-by-side in harmony, without the need for any compositional design.

Three Lines with Arabesque

In the 1990s, Griffa set a rule that would become the name of a new cycle and the common denominator shaping each of the works themselves—to contain three lines and an arabesque. The outcome shows a surprising freedom, diversity, and variety. To give each work a unique identity, Griffa decided to number each canvas in chronological order of their painting. Thus numbers made their first appearance in Griffa’s work, not as a decorative motif but as a means of ordering the individual elements—the canvases—of the cycle itself.

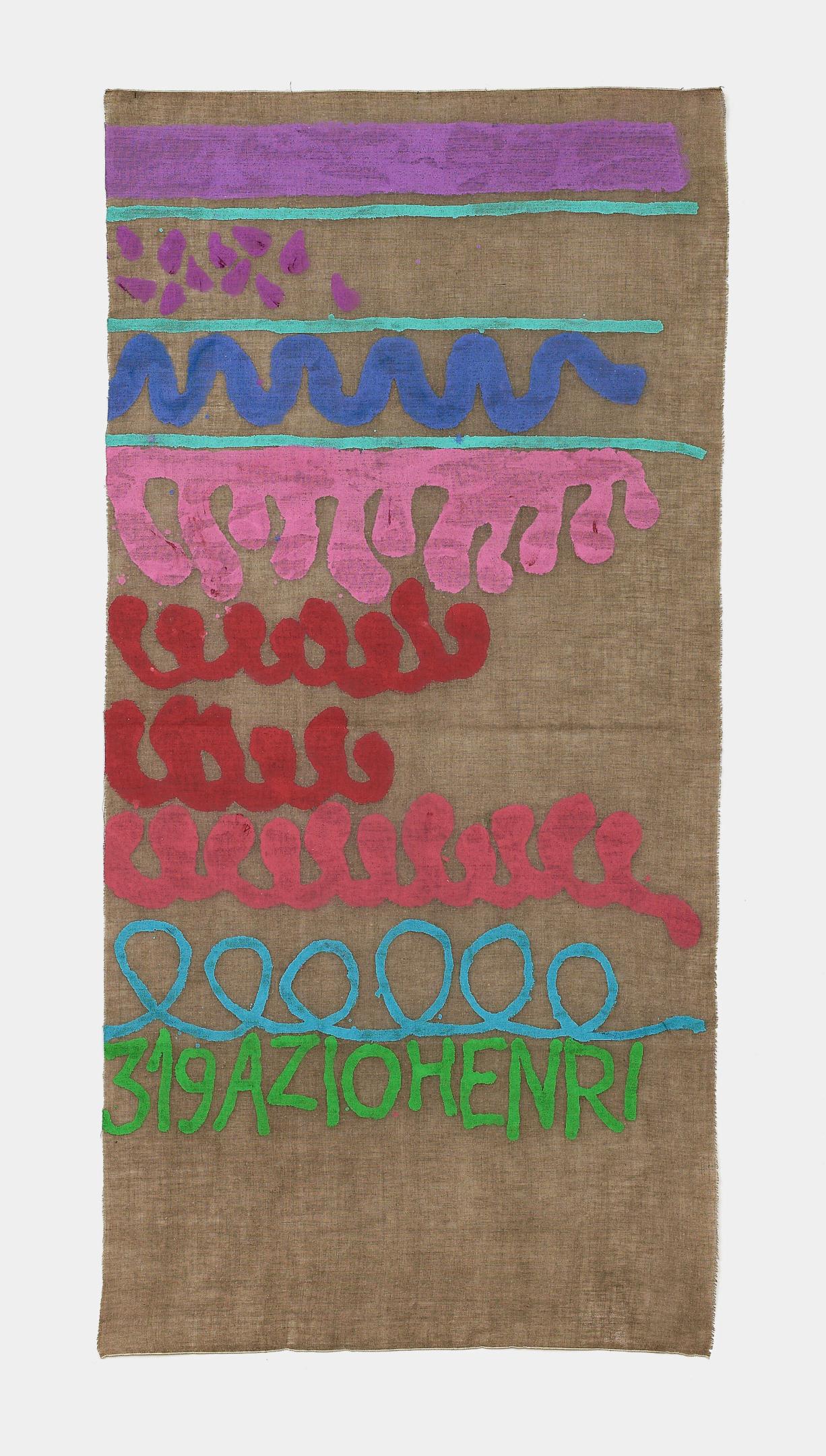

Numbering

The Numbering cycle took shape in the 1990s, shifting the focus on the internal patterns that give rise to each single work—sign after sign, rhythm in time and space. The progressive numbers mark the order with which the signs and colors were painted on each canvas in the cycle.

Golden Ratio

In the early 2000s, Griffa began to focus on the golden ratio, the divine proportion conveying the mystery of the beauty and equilibrium found hidden in nature and art across the ages. It is an irrational number that decimally expands to 1.61803398874989484820... forever to infinity in space and time. The golden ratio challenges the limits of human reason, ushering us into the unknown. It is an extraordinary metaphor for the task assigned to figurative art, poetry and music ever since the age of Orpheus—to probe the unknowable and speak the unspeakable.

Shaman

Around 2018, Griffa began exploring a new path into the hidden world, not through numbers but through words. In the footsteps of the ancient shaman murmuring incomprehensible words, Griffa uses nameless words on the canvases to open up a door to the unknown, to that part of the world without name or identity. Just like for the shaman, it is reason that plots the path beyond the boundaries of reason itself.

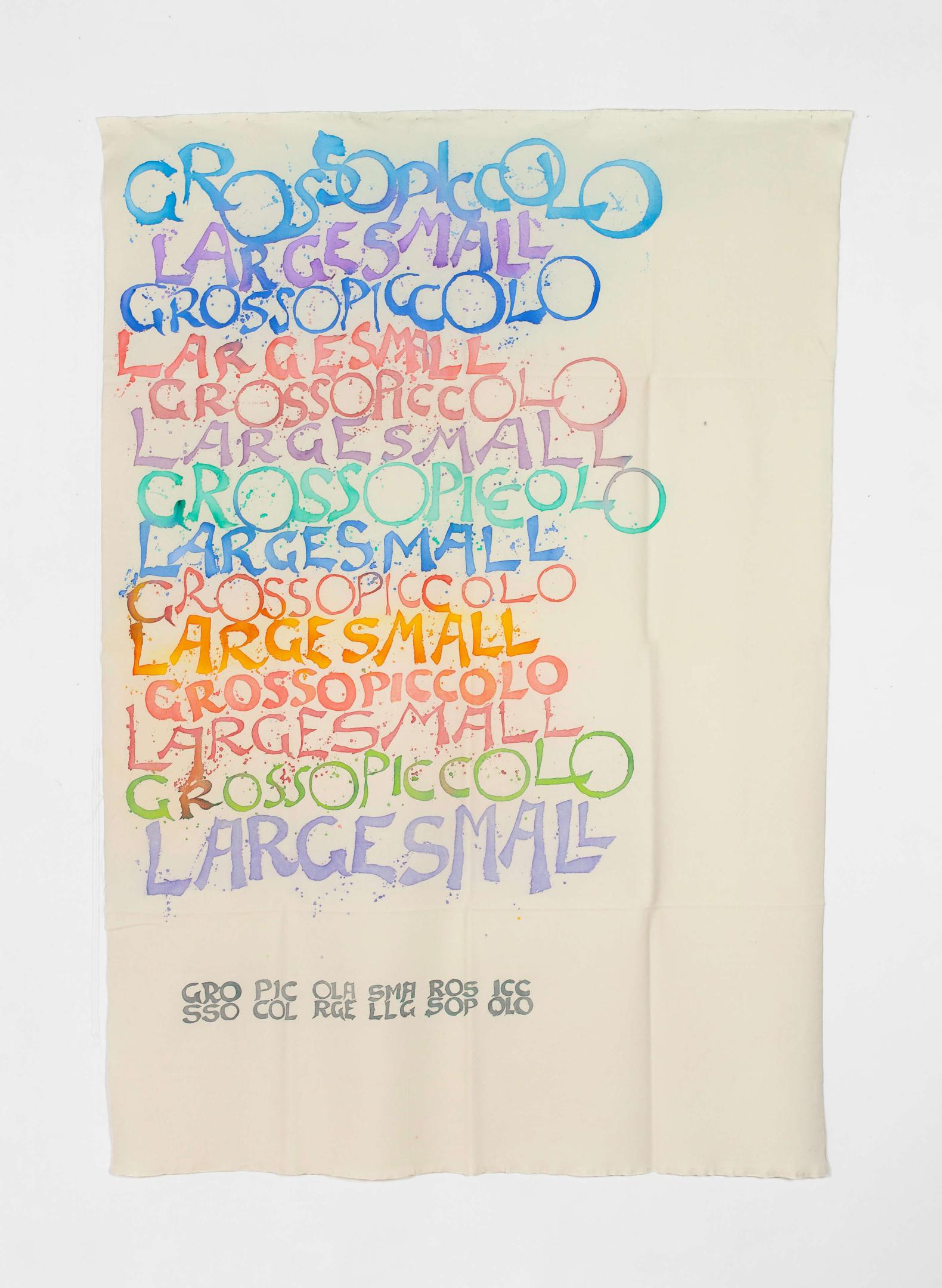

Dilemma

The Dilemma cycle came about in parallel with Shaman, embracing both horns of the dilemma of classical Greek philosophy, just as they are embraced in painting and the world it depicts. Here the two horns of the dilemmas of everyday life become one word on the canvases and in their titles—newold, topbottom, frontback, uglynice, activepassive, lightdark, alwaysnever. It is also a way of embracing and celebrating the contradictions that Griffa holds are foundational in his painting, where the passive attention shown to what is unfolding stands side-by-side the active gesture of the artist making the signs on the canvas, where anonymous signs give shape to a painting that is anything but anonymous, where the unfinished is instantiated in finished works, and so on.

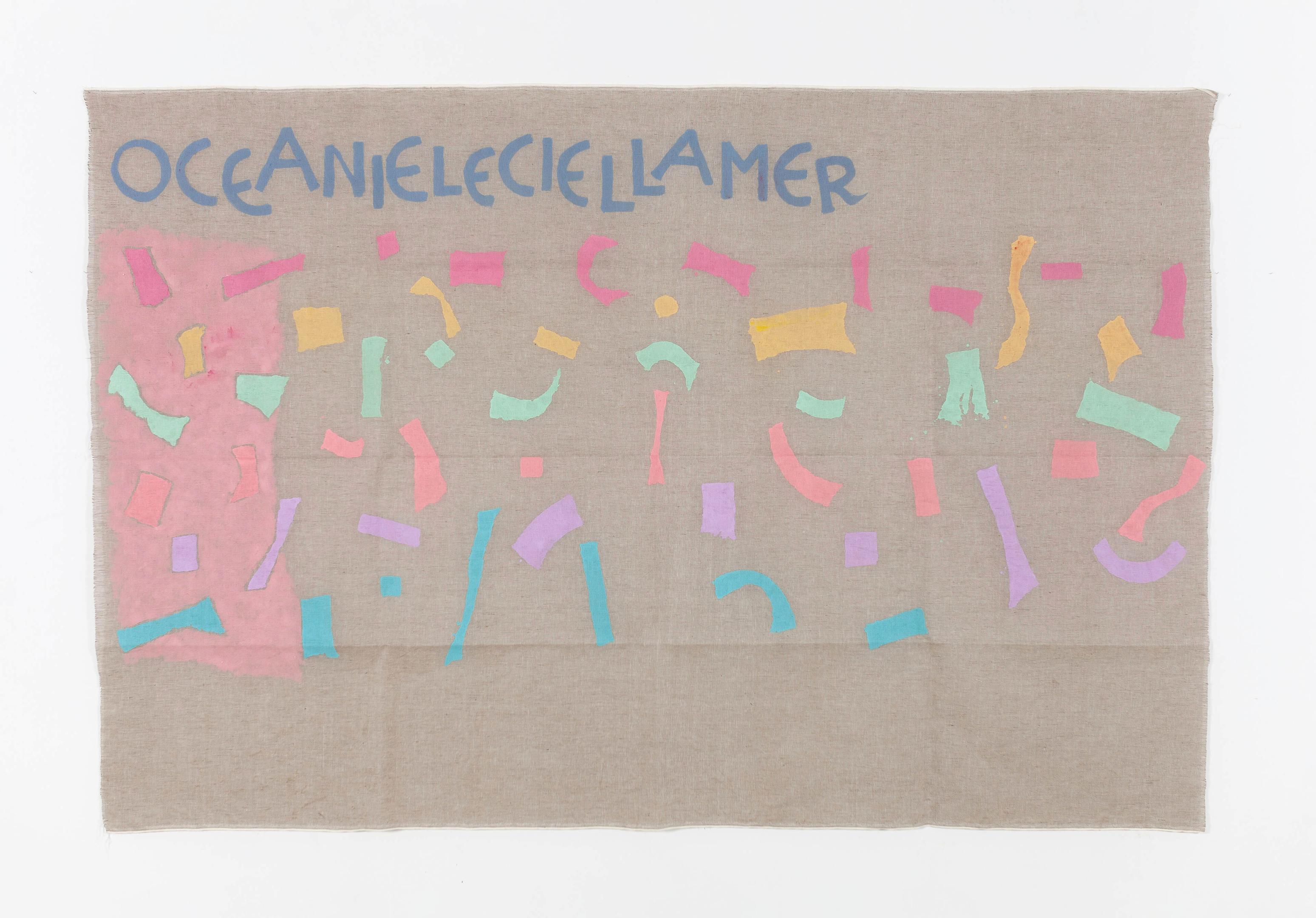

Océanie

This cycle developed in 2022 from two Alter Ego canvases dedicated to Océanie, La Mer and Le Ciel by Matisse, which for Griffa symbolically mark the passage from Newton’s perfectly mechanical universe to our own quantum mechanical universe. Perfect order has given way to a beauty that is astonishingly complex and ungraspable, which our concept of perfection is entirely unable to convey.

Disorder

The most recent cycle to take shape, in 2023, is Disorder, in which Griffa reflects on giving order to disorder and how the crystallization of disorder is the beginning of a new order. Sometimes order constructs disorder, which in turn constructs new order, which constructs new disorder, which constructs new order, and so on to infinity. Even that is a representation of the world. The works in this cycle are identified by groups of letters, much like the license plates on cars. The first is Disorder AA, the second, Disorder AB, and so on.